Brooklyn and Uptown :

Prologue:

If you were to drive through Uptown today, you will see tall towers, parks, wide-open plots of land, and construction. But at one point in time, driving through it looked completely different.

This is the story of Brooklyn. Follow us as we explore this once a thriving African American neighborhood, what happened to it, and its future!

Beginning:

Situated in Charlotte’s Second Ward, Brooklyn was downhill from Uptown. Making life in the area harsh because in the late 19th century, sewers were not widespread and areas downhill were prone to get that runoff. In the late 18-hundreds, the area was known as Logtown; a place where recently emancipated slaves took up residence. As the 20th began, the population was solidly African American. And It was not until the mid-1910s that Logtown would become generally known as Brooklyn.

It was during this period that Brooklyn started to develop into a thriving, self-sustaining community. The neighborhood’s housing supply ranged from shanty towns to the grand homes of black professionals.

Where Biddleville was centered around higher education and was an bordering area of the city, Brooklyn was the Main Street for Charlotte’s African Americans. Many important landmarks in the community include the Myers Street School (Charlotte’s first black public school 1886-1907), the city’s black YMCA, a Library for blacks, and much more.

Brooklyn was the reaction of the systematic oppression and disenfranchisement by the powers at the time. There was a need to provide opportunities, services, and political clout for black Charlotteans.

Blacks also flocked to Brooklyn for affordable and available housing. This was a side-effect of red lining. The private and federal systems set up to prevent African Americans and other minorities from living or buying homes in white neighborhoods. By the 1940s the federal government began programming mortgages for the west side of Charlotte for Blacks. This had the consequence of draining the neighborhood of its residents. Another blow to Brooklyn was the construction of Independence BLVD, which cut a swath out of Brooklyn and highlighted the remaining devastated areas.

Additional Reading:

https://uncc.worldcat.org/title/brooklyn-story/oclc/6614067

http://www.charlottemagazine.com/Charlotte-Magazine/September-2014/Memories-of-Brooklyn/

https://brooklynvillage-clt.com/history/

Important sites and historic buildings:

Something that is almost as important as those who make it up are the landmarks. These important places and buildings hold the memories and emotions of numerous individuals. Whether it is the first day of school, a moving sermon from the pastor, or the start of a new venture. Before the decimation of the neighborhood, Brooklyn was home to many key buildings and institutions. Let’s take a tour of what was.

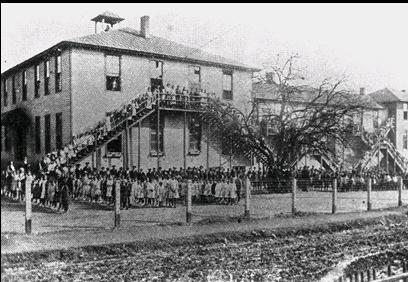

Holding its first classes in 1886, the Myers Street was opened to fill the gap in public education for African Americans in the city. By 1940, the school had grown to become the largest school for blacks in the entire state and earned the nick name the Jacobs Ladder School because of a set of stairways that were added as fire escapes. Because of segregation ramping up in the early 20th century, many black families from around the county moved to the neighborhood to afford their children an education. The school remained open until 1960s, when the building was demolished to make way for “Urban Renewal.” The site where the school was is now a part of Mecklenburg Aquatic Center and the Metro School. Another school of prominence in the Brooklyn community was Second Ward High School. The high school opened up in 1923 some 40 years after Myers Street. The school was located on Alexander St. and was the first public high school for blacks in the County. Before, to get a secondary education, blacks would have to move to a different school district or go to Johnson C. Smith University.

Mecklenburg Investment Company Building:

Constructed in 1922, the Mecklenburg Investment was built by and for Charlotte’s black community. Since Jim Crow laws prevented Blacks from leasing business space in communities where they were not welcome there was a need to create a space where black entrepreneurs could thrive. Spearheaded by an investment of group of leaders in the neighborhood, the building’s purpose was to be the center of neighborhoods economic engine. The main investors included doctors, dentist, and HBCU faculty. One main investor was Dr. J.T. Williams, a person who is explored later in the episode. Over the next 80 years the Building would eventually become home to many businesses, such as Yancey’s Drug Store, doctor’s offices, a hotel, and clubs. But by the close of the Civil Rights era, integration meant an opening of commercial space to businesses of color. This caused many tenants to abandon their space at the building. If you are ever uptown, building still stands at 233 s. Brevard St.

A few other important sites that once stood in Brooklyn are

Brevard Street Library: Built in 1905, the library was among the first to serve african americans in the county. It was built by funds from Charlotte and donations from the community.

Grace AME Zion Church: Still standing at 219 S. Brevard St., the Gothic Revival structure was built in 1901 and was listed to the National Register of Historic Buildings in 2008.

Additional Reading:

https://www.cmstory.org/sites/default/files/images/1969%20students.jpg

https://www.cmstory.org/sites/default/files/images/JacobsLadder_0.jpg

https://www.cmstory.org/sites/default/files/images/1918SixthGrade_0.jpg

Second Ward High School National Alumni Foundation - http://www.secondwardfoundation.org/

http://www.cmhpf.org/educationneighhist2ndward.htm

http://www.cmhpf.org/educationneighhistcentercity.htm

https://www.charlotteobserver.com/news/local/article57611168.html

Further Landmarks:

Mecklenburg Investment Company Building.

Little Rock AME Church 1st ward

Myers street school

Second ward high school- http://secondwardfoundation.org/homepage

Old colored YMCA

AME Zion publishing house -

Grace AME Zion Church

Black Main Street: A Place of Excellence:

The political and economic disenfranchisement that blacks experienced in the US during the early 20th century, led to a push back of sorts. Increasing unwelcome in many public areas across the south, Black Main Streets began popping up in America’s urban areas. Black leaders during this time preached self-sufficiency. If they were going to be excluded from the economy, they would create one of their own. This led to pockets of businesses that catered to the needs of African Americans, and Charlotte was no exception. Business owners driven out of predominately white neighborhoods by rising rents and segregation, flooded the Brooklyn community.

People Like J.T. Williams, the son of a freed slave who ran a successful lumber business in Cumberland County, moved to Charlotte in 1882, after studying to become a teacher at what is now Fayetteville State University. Williams was among the faculty that founded the Myers Street School, as the first public school for African American Children. After teaching for three years, Williams went on to attend Shaw University’s Leonard Medical School in Raleigh, and in 1886 he returned to Charlotte as a Doctor one of one of the first 3 black doctors licensed in the state of North Carolina. Williams would go on to work with other important figures in the Brooklyn community to found Grace Zion AME Church and the AME Zion Publishing house.

Additional Reading:

https://guides.library.uncc.edu/c.php?g=621704&p=4626874

http://mainstreet.lib.unc.edu/projects/bearden_charlotte/index.php/images/view/50

https://www.cmstory.org/exhibits/african-american-album-volume-2-places/s-brevard-st-400-blk

https://www.cmstory.org/exhibits/african-american-album-volume-2-places/s-brevard-st-200-300-blks

Other noticeable figures from Brooklyn’s history are:

Kelly Alexander Jr. – A Democratic NC General Assembly member serving the 107th district. His father served as Chairman of the Board of Directors of the NAACP. Senior was also a figure in Charlotte’s civil rights struggle. Kelly Alexander Jr. was Frederic Alexander’s nephew.

Thad Tate – A business and civic leader in Charlotte, living from 1865 to 1951. He came to Charlotte in 1877 running a barber shop in Uptown. His patrons included many prominent leaders such as “Governor Cameron Morrison, the store owners William Henry Belk and J. B. Ivey, and the neighborhood builder Edward Dilworth Latta.” This proximity to city and state leaders gave Tate the opportunity to get improvements for the black community, including schools, a YMCA, and a library. He was a founding member of the Mutual Insurance Company created to focus on African Americans. He also helped build the Mecklenburg Investment Company Building.

Sallie Phelps – A librarian at the Brevard Street Library for Negroes.

William W. Smith – A prominent African American Architect, Smith was instrumental in what is called “Charlotte’s Negro business Renaissance.” He designed and built Graze AME Zion Church and its publishing house, Goler Hall at Livingstone College, and the Mecklenburg Investment Company building.

Rose Learly Love – Love was a writer, and teacher who grew up in Brooklyn. Her works include “Plum Thickets and Field Daisies” which dives into the daily life of the Brooklyn neighborhood. It is a great read and I encourage you to read it. It is available for free online; link is in the show notes

“Urban Renewal:”

For the next few decades, Brooklyn flourished. A mecca of Black commerce in the face of open discrimination and segregation, this area, however, would not last forever. In the 1930s, with little to no representation in government, a program was started to offer African Americans mortgages only in certain parts of Charlotte. With the allure of new housing, Brooklyn began its decades long purge. The next cut to Brooklyn’s success was the construction of a new road, Independence Boulevard. Built strategically to demolish sections of the neighborhood, the highway was part of a growing trend in urban development to segregate cities with the use of features such as freeways and other manmade landmarks. It was also built to ferry white suburbanites to their offices downtown without having to suffer the experience of driving through black neighborhoods. By 1947, decades of neglect and underdevelopment was showing its face. The federal government set aside money for “Urban Development.” Emboldened, Charlotte began to rezone the entire neighborhood as industrial even though the entire area was residential.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Planning Commission was formed in 1958 to determine if blight had occurred within Brooklyn to receive federal money. Some of the findings found in their report were that the area needed “renewal” because of ‘rude and primitive’ homes, decrepit streets, and overcrowding. North Carolina law at the time stated that a community was considered blighted if 2/3rds of housing was dilapidated. Under this definition, Brooklyn was 77% blighted. This was all the federal government needed and over 1 million dollars was allotted to clear the neighborhood. The Charlotte Redevelopment commission created a pamphlet titled the “Brooklyn Area” with one page calling the old neighborhood a “A social and economic liability in 1960” and the new neighborhood “by 1970 An Asset.” Part of the plan called for a relocation effort to move the displaced residents to newer areas, but this was not the truth. There were reports of residents being extorted, pushed out with no home to go to. With no public housing for the poorer families of Brooklyn, 90% of whom were black, there was suspicion that this was done intentionally to segregate blacks. Despite objections from the NAACP and residents the plan to raze the neighborhood moved forward.

From 1960-67, Brooklyn was demolished. In between this time, no homes were built to replenish what was lost. Over 1000 residents were left out on their own. In fact, the renewal that would replace Brooklyn was not meant to be residential. Instead it was meant to be populated by government buildings, parks, and some office buildings. It would remain that way until the 2010s.

Primary Source:

https://guides.library.uncc.edu/c.php?g=621704&p=4626874